Introduction

When you touch your phone to unlock it, you likely imagine the device comparing a photograph of your finger against a master photo stored in a secure vault. You imagine a perfect match: 100% or nothing.

This is a lie.

In reality, your biometric security is a game of statistical probability. The scanner isn't looking for "you"; it is looking for a mathematical probability that the person pressing the sensor is close enough to you to be let in. From the "MasterPrint" vulnerabilities to the $15 "BrutePrint" device that can crack Android phones, the mechanism of fingerprint recognition is far more fragile – than the manufacturers admit.

This article peels back the marketing to reveal the actual engineering (and flaws) behind the sensor.

Acquisition & The "Cleaning" Phase

Before the math begins, the physical data must be captured. In the academic world, this is known as Image Acquisition. However, raw data is rarely perfect.

As highlighted in technical surveys on fingerprint recognition, captured images are frequently corrupted by noise-creases in the skin, smudges on the sensor, or "holes" in the ridge data due to dry skin. If a scanner relied solely on the raw image, it would fail constantly.

High-trust systems perform a rigorous "cleaning" phase before they even attempt to identify you.

Fourier Transform (FFT) & Wiener Filtering: The system applies complex algorithms (like Grey-level smoothing and contrast stretching) to artificially boost the contrast between ridges and valleys.

Masking: The software identifies "unrecoverable regions" (blurred or too dirty) and masks them out, ensuring the system only processes high-quality data.

The Sensor Types:

Optical Scanners: Capture an image of friction ridges using light (Level 1 features).

Capacitive Scanners: Use electrical current to map the finger, effectively ignoring the "visual" noise that fools optical sensors.

Ultrasonic Scanners: The gold standard, capable of mapping even Level 3 details (see below).

Fingerprint Extraction Levels Explained

Most consumer guides oversimplify this process. A truly secure Automatic Fingerprint Recognition System (AFRS) doesn't just look for "points." It breaks your identity down into three distinct levels of feature extraction, a standard protocol in biometric engineering.

Level :

The Macro View

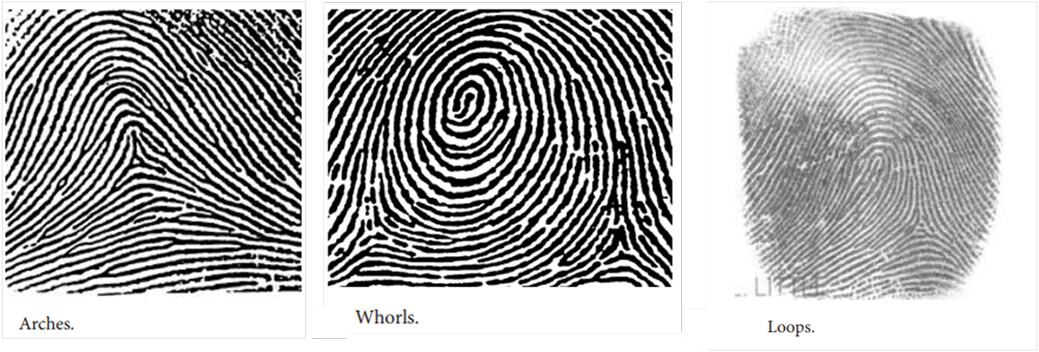

First, the system looks at the overall flow of the ridges. It classifies your print into one of three major archetypes:

Loop

Delta

Whorl

Limitation: This level is used for broad classification (Pattern-based matching) but is not unique enough to identify a specific person.

Level :

The Minutiae

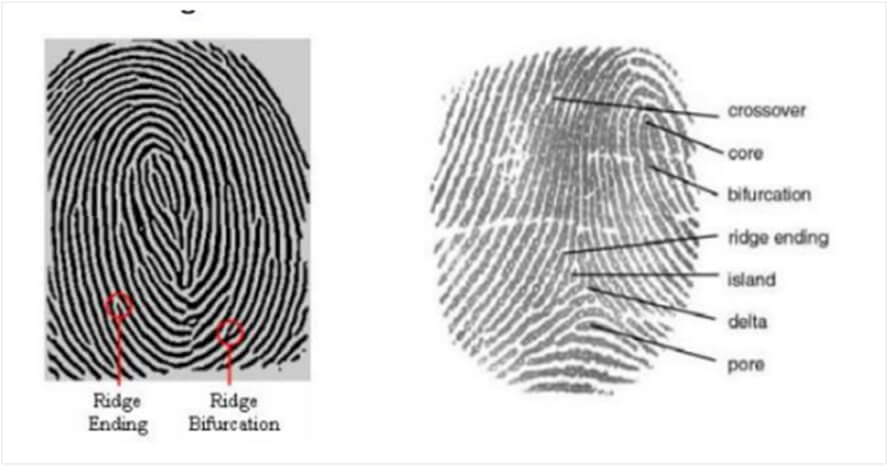

This is the standard for most smartphones. The system identifies specific "abnormal points" on the ridges, known technically as Minutiae. While most people know about ridge endings, the academic taxonomy is far more detailed:

Ridge Bifurcation: A single ridge splitting into two.

Lake (Enclosure): A ridge that splits and rejoins.

Spur & Crossover: Irregularities between ridges.

Islands: Tiny independent ridges.

Level :

The "Sweat Pore" Standard

This is where high-security government scanners differ from cheap phone sensors. Level 3 extraction detects intra-ridge details, specifically the placement of sweat pores (white pores on the ridge). These are microscopic and extremely difficult to fake with a gelatin mold or a 2D photo.

Correlation vs. Minutiae

Here is where the "security" becomes "probability." The system performs a comparison to generate a score. According to foundational research in biometric techniques, this matching generally falls into three families, each with its own vulnerabilities.

Investigative Deep Dive

The reliance on "probability" rather than "exactness" has led to significant security exploits that mainstream tech news rarely covers in depth.

-

The "MasterPrint" Attack

Researchers at NYU found that because phone sensors are small, they only scan a partial fingerprint. They discovered that certain generic ridge patterns (loops and whorls) are so common that they appear in roughly 65% of people.An artificial "MasterPrint" containing these common features can successfully unlock significantly more devices than a random finger, acting like a "skeleton key" for biometric locks.

-

The "BrutePrint" Exploit (2024-2025 Era)

In a terrifying development, researchers from Tencent Labs and Zhejiang University developed BrutePrint.

A $15 circuit board bypasses the "attempt limit" (the rule that locks your phone after 5 failed tries). By exploiting a flaw called "Cancel-After-Match-Fail," the device can try infinite fingerprint variations against your phone until it finds a match. It essentially "guesses" your fingerprint the way a hacker guesses a password.

This successfully cracked nearly every Android device tested, though iPhones remained resistant due to encrypted data paths.

Can a Template be Reversed?

For years, companies have claimed: "Even if hackers steal the database, they only get useless numbers. They cannot recreate your fingerprint."

This is scientifically false.

Recent research into Deep Learning Reconstruction has shown that AI can take a "useless" minutiae template and reconstruct a fingerprint image that is accurate enough to fool a scanner.

If a corporate database of biometric templates is breached (like the OPM breach or various banking leaks), hackers >can potentially generate physical fake fingers that work on your personal devices. Unlike a password, you cannot change your fingerprint when it is compromised.

Final Thoughts

Fingerprint scanners are a marvel of convenience, but they should not be mistaken for perfect security. They are efficient at keeping out your nosy spouse or a random thief, but against a targeted attack using tools like BrutePrint or AI reconstruction, the math begins to crumble.

For the average user, the advice is simple: If you are in a high-risk situation (border crossing, protest, or holding sensitive corporate data), disable biometrics. Rely on a strong, complex alphanumeric passcode. A password exists in your mind; a fingerprint exists on every glass you touch.

FAQs

Generally, no. Modern capacitive and ultrasonic scanners often use "liveness detection" (checking for blood flow or electrical conductivity) which disappears shortly after death. However, older optical scanners can potentially be fooled.

Ultrasonic scanners (found in high-end Androids) are currently considered the most secure consumer option because they map 3D depth, making 2D spoofing (photos) impossible.

For consumer devices (Apple/Samsung), the data is stored locally on the device's chip (Secure Enclave). However, for employer time-attendance systems or government IDs (like Aadhaar), the data is often stored in a centralized server, which poses a higher hacking risk.

It is the percentage of times a biometric system incorrectly identifies an unauthorized user as the correct person. A secure system aims for a FAR of 1 in 100,000 or better.

No. This is the "biometric paradox." Once your biological data is compromised, it is compromised for life. You cannot update your fingerprints like you update a password.

Comments