Introduction

For over a century, the fingerprint has been the gold standard of identification. But in the real world, where hands are calloused by labor and skin ages, that standard is failing. Two massive, unrelated identity systems – the U.S. Border Patrol's screening process and India's Aadhaar national ID program – are reaching the same conclusion: when identity is critical, fingerprints are not always enough.

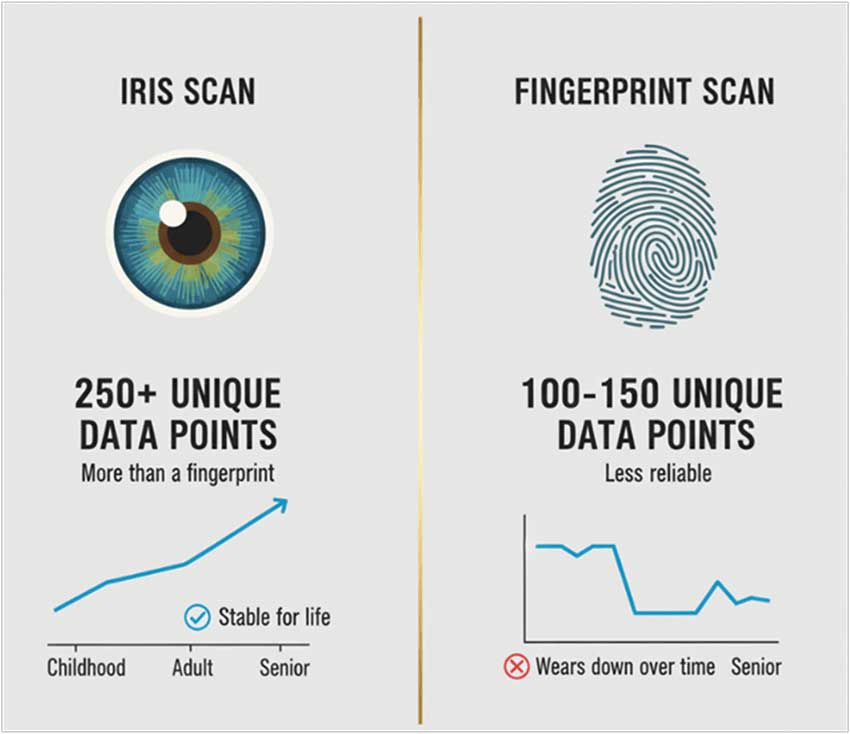

To put this into perspective, a technical upgrade is slowly becoming a fundamental shift in how we verify identity, driven by the urgent need for a more inclusive and reliable solution. The technology stepping up to fill the gap is iris recognition.

What Happened at the U.S. Border?

The core problem with fingerprints is their fragility. In high-stakes environments, this fragility translates into systemic failure.

At the U.S. border, agents have long dealt with what they call the "burned fingerprint problem." The fingerprints of migrants who have performed years of manual labor are often worn smooth. Others are damaged by cleaning chemicals or, in some cases, intentionally altered. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has found iris scanning to be a critical tool, successfully making thousands of identifications where fingerprints were unreadable. This has prompted a significant expansion of iris scanning technology across its checkpoints.

This challenge is mirrored on a massive scale in India. The Aadhaar system, which covers over a billion people, has documented significant authentication failures, particularly among manual laborers, farmers, and the elderly. Reports have highlighted how construction workers, and agricultural laborers are frequently locked out of essential services like food rations and banking because their life's work has "sanded away" their fingerprints.

As one Border Patrol official noted, the iris provides a reliable way to create a biometric record when fingerprints simply "won't work at all."

An official from India's identity authority, UIDAI, acknowledged the issue, stating that fingerprints "do get erased or changed" with age and manual work. The problem isn't limited to manual laborers; even common conditions like excessive sweating (hyperhidrosis) or the natural fading of ridges in old age can render fingerprints useless for authentication.

Also Read - Difference Between Iris Recognition & Retina Scanning

Iris Scanner is More Reliable Than You Think

The shift toward iris recognition is based on its clear biological and technical advantages.

Fingerprint wear can block access to social benefits. Iris scanning ensures identity stays intact.

The Rise of L1 Devices

Modern biometric systems are not just about capturing an image; they are about securing the data from the moment of capture. India's UIDAI has driven this change by mandating a new generation of "L1 Registered Devices" for both fingerprints and irises.

Unlike older devices that sent raw biometric data to a host computer for encryption, L1 devices have security built directly into their hardware. They use a Trusted Execution Environment (TEE to encrypt the biometric data instantly. This means the unencrypted data never touches the vulnerable operating system of a computer or mobile device, drastically reducing the risk of hacking or tampering.

This architectural shift is quietly creating a secure foundation for the next wave of digital identity.

Also Read - Iris Recognition: What No One is Talking About

Dual-Modal by Default

The solution isn't to replace fingerprints entirely but to create a more resilient system where both modalities work together. This "dual-modal" approach is becoming the new best practice.

Both UIDAI in India and the U.S. Border Patrol are moving toward this model. The goal is a system where an iris scan is not just a backup but a co-primary method of identification, ensuring that everyone can be identified correctly and humanely.

The Mantra of Affordable Iris Technology

India's iris scanner deployment succeeded where others failed because of aggressive local manufacturing. Companies like Mantra became UIDAI's backbone by producing devices that balanced cost, accuracy, and field durability.

MIS100V2:

The workhorse single-iris scanner deployed across Aadhaar enrollment centers. Uses CMOS sensors calibrated to capture iris patterns from under one meter away, with auto-focus and LED distance indicators to guide operators.

MATISX Dual Iris Scanner:

High-security applications demand dual-eye capture for depth verification and liveness detection. MATISX uses stereo imaging to detect whether both eyes belong to the same person in real-time, preventing printed photo attacks. Deployed in border checkpoints and financial institutions where spoofing risk is elevated.

Final Thoughts

The story of the "burned fingerprint problem" is a powerful reminder that technology must be designed for the complexities of human life. A person's right to access services, cross a border, or prove their identity shouldn't depend on whether their hands are calloused or smooth.

Iris recognition offers a path to a more equitable and reliable biometric future. While no technology is perfect, the stability of the iris provides a fairness that fingerprints cannot. The technology is ready. The need is clear. The remaining challenge is the will to build systems that prioritize people over institutional inertia.

FAQs

Not with modern, certified devices. They use "liveness detection" to look for subtle cues like pupil dilation, corneal reflections, and micro-movements that are absent in a static photo. Advanced systems can also detect textured contact lenses designed to mimic an iris pattern.

When Aadhaar launched, the cost of iris technology was prohibitive for enrolling over a billion people. Fingerprint scanning was a more economically viable starting point. The shift is happening now due to lower technology costs and a decade of data proving the need for a more reliable alternative.

Yes. Certified scanners use a low-intensity, near-infrared light source, similar to a television remote control. The light levels are well within international safety standards and pose no risk to the eye, even with repeated use.

In rare cases, official protocols like UIDAI's allow for a "biometric exception." Identity is then verified through other means, such as a photograph and demographic data, with authentication often relying on a one-time password (OTP) sent to a registered mobile number.